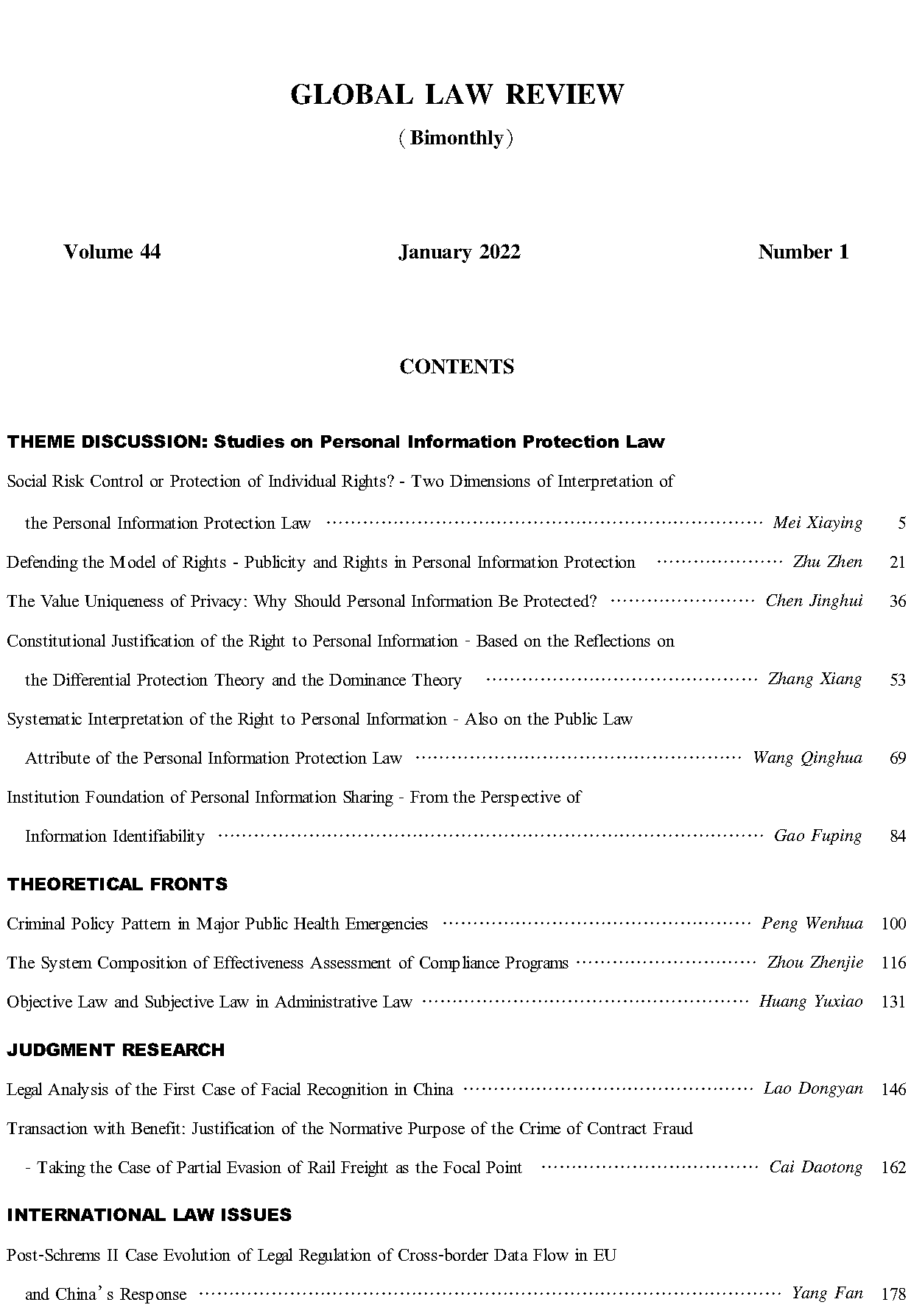

Social Risk Control or Protection of Individual Rights? - Two Dimensions of Interpretation of the Personal Information Protection Law

Mei Xiaying

Abstract:Chinese Civil Code recognizes personal information as a kind of personality legal interests, thereby establishing the private law protection orientation of personal information in theory and legislation and making the protection of personal rights and interests an important dimension of and a clue to the construction and understanding of personal information protection. Personal information protection laws around the world have sought to improve the path of personal information protection from different dimensions, and these paths are not mutually exclusive, but are all based on a major value orientation or starting point, which in turn covers all possible ways and means. At present, the public objectives and functions based on personal information protection cannot be covered or eliminated by the approach of personal private interest protection, so it is necessary to recognize social risk control as an important dimension of personal information protection. Social risk control has always been the basic objective of personal data protection in the electronic era. It has a strong explanatory power and plays the role of dynamic construction in the relevant theories and systems of personal information protection. There are contradictions between the social risk control approach and the personal rights protection approach on some basic issues, such as the basic relations between personal information and privacy, between general protection and scenarized protection, and between the right itself and the protective right. In the future implementation of the Personal Information Protection Law, the social risk control approach is conducive to reasonably interpreting and implementing the law, achieving the reasonable matching between the scale of risk and control measures, such as the matchings of different risk dimensions and corresponding restrictions for data security, data migration and facial recognition. In the meantime, the mobility of information should be released on the premise of balancing the relevant legislative values. For example, for the application scope and exclusion rules of personal information protection, the right to deletion of personal information subjects and the legitimacy basis of personal information processing, the corresponding application scopes and exclusions should be balanced according to the corresponding risk matching degrees. In short, with the development of cyber technology and its application, new risks continue to emerge, are iteratively updated along with technological development, and bring new challenges to humanity. The method of thinking and construction of risk dimension is very important in the field of personal information protection, because the law can only confirm and regulate the existence of personal information rights and interests once, and for the states of continental law system, the stability of law may conversely imply a rigidity, but the risks in the use of personal information are unpredictable or even infinite. Therefore, the thinking and institutional construction in the risk dimension is more important and worthy of attention.

Defending the Model of Rights - Publicity and Rights in Personal Information Protection

Zhu Zhen

Abstract: The rights model and power model of personal information protection are two opposite models. Scholars generally believe that specifying the right to personal information is equal to giving individuals exclusive control, but this belief contradicts the publicity of personal information. Therefore, personal information cannot become a right, but can only become an object of legal protection. Even if it can be recognized as a right, it is only a right to legal protection of personal information. In the era of big data, the existence of personal information is indeed public, but this does not mean that social control should replace personal control, because publicity in this sense does not necessarily oppose the right model. This has been illustrated by the legislative practices of the dignity-based basic human rights protection model in the EU and the property protection model in the US. Indeed, the publicity in a broad sense includes the public interests borne by personal information and the publicity of personal information is also a prerequisite for personal and commercial communication in the network era. However, this does not mean to deny the right protection mode of personal information. Public interests (or common goods) are diversified, and some of them can support individuals to enjoy the right of information. An effective protection model is the result of the balance of various public interests, rather than one-way social control. Therefore, there is no single individual control or social control in personal information, rather a balance under the control of law. In this balance, the right to personal information still has independent value. The rights model has many advantages. It is conducive not only to establishing an open system of right protection, but also to balancing the rights and powers among various subjects, so as to have continuous information input, form a constantly updated information resources system, maintain the value of information and prevent it from degradation. The claim contained in the right ultimately guarantees human dignity and freedom, which is also the fundamental purpose of the personal information protection law. The “right to the protection of personal information” is unable do this. It does not have the direction of obligations and only constitutes a conceptual background of “personal information” legislation, that is, personal information should be protected. In the normative model of legislation, the personal information protection law is still dominated by obligatory norms or prohibitive norms, which is determined by the nature of personal information in cyberspace. It is of no practical significance for individuals to claim rights and remedies in the network era, but this does not contradict the rights protection law attribute of the personal information protection law.

The Value Uniqueness of Privacy: Why Should Personal Information Be Protected?

Chen Jinghui

Abstract: To accurately understand the newly adopted Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, we must properly answer the question of “why personal information is worth protecting”, which is often associated with the value of “privacy”. However, the theoretical understanding of privacy or the right to privacy is currently dominated by a reductionism which holds that privacy does not have unique value. Judith Jarvis Thomson, as the main representative of reductionism, insists that all violations of privacy can eventually be reduced to violations of proprietary rights relating to personal ownership or property. This is because, on the one hand, the object of “knowing me” is my information, which must be the facts or the truth about me, and I am not afraid that the facts or truth about me are known by others, which means that simply knowing me will not infringe on my privacy; on the other hand, since not all knowledge of me is harmful to my privacy, there must be some ways of knowing me that infringes on my privacy, and only the ways of knowing me that infringes on my personal right and my property right at the same time constitute an infringement on my right to privacy. Therefore, in order to justify the value uniqueness of privacy, we must completely defeat the reductionism. This paper raises two arguments: first, even if the information about someone belongs to facts or truth, it does not make the fact-hiding or truth-hiding the moral wrong of cheating, and the state or the community may not demand everyone to take the initiative to expose their own facts or truth. Otherwise, the individual will become a naked survivor, like animal, or the prisoner of a huge jail in this community, and it will not be reasonable to think that civilization could emerge, be sustained and flourish in this community. Second, more importantly, merely “knowing the facts or truth about me” is still an infringement on the key interest or right of my privacy, because “the facts or truth about me” determines “who I am”, which is related to my “appraisal respect”, which is obviously distinct from the “recognition respect” about “I am a human being”. Moreover, the more you know the facts or truth about me, the more serious damage will be brought to my recognition respect, so we can conclude that the knowing is harming. If the above two arguments are finally established, the reductionism, which insists that privacy does not have value uniqueness, will fail completely. In short, the value uniqueness of privacy means that, for any specific individual, only privacy can provide the appropriate treatment of him “as a human being”, which is very important for him to gain more recognition and respect. Otherwise, his dignity will be seriously damaged.

Constitutional Justification of the Right to Personal Information - Based on the Reflections on the Differential Protection Theory and the Dominance Theory

Zhang Xiang

Abstract: The private law understanding of the protection of personal information played a fundamental role in the development of the personal information protection system in China. In legislative debates over the Personal Information Protection Law, whether to add the expression “in accordance with the Constitution” in the law was a very controversial issue. This expression was added to the law in its third draft, signifying the change of the underlying logic of the personal information legal protection system. The Personal Information Law is a basic law in the field of personal information protection, rather than a branch of civil law. Because of the high degree of asymmetry of the relationship between the individual and the information processor, the high frequency of information transaction, and the spillover of processing risks, personal information processing in modern society has gone beyond the traditional private law relationship between equal subjects. Therefore, the theoretical distinction between rights and interests in civil law cannot be applied to the constitutional protection of personal information. This paper suggests that the right to personal information be established as a fundamental right, and as both a subjective right and an objective value order above the whole legal system and used to coordinate the private law mechanism and public law mechanism for the protection of personal information. The right to personal information is in nature a bundle of rights, which can be justified by interpreting the human rights clauses on the freedom of personal communication and human dignity. Firstly, the freedom and privacy of correspondence is a constitutional basis of the protection of personal information. Secondly, the right to personal information can be theoretically incorporated into the scope of protection of human rights clauses in the Constitution. But considering its generality, this right should be interpreted in conjunction with other concrete rights to make it more operable. Thirdly, the right of human dignity provided for in Article 38 of the Constitution is also a constitutional basis of the protection of personal information. A person should not be spied upon, mentally oppressed, manipulated, discriminated against, or exploited in the processing of his/her personal information. Therefore, a differentiated multi-level structure is necessary for the protection of personal information. The dominance theory on the protection of personal information has limitations, as is indicated by the decline of the notice-and-consent mode. In this sense, the goal of the protection of the right to personal information should be adjusted as ensuring the free development of human dignity without intervention by others. The switch from the dominance theory to the theory of development of human dignity is conducive to regulating the use of collected information, breaking the information cocoon, easing the tension between the protection and the appropriate use of personal information, and effectively guaranteeing the self-determination of the individual within the individual-platform-state relationship, while preserving enough space for the development of the data industry.

Systematic Interpretation of the Right to Personal Information- Also on the Public Law Attribute of the Personal Information Protection Law

Wang Qinghua

Abstract: The development of information technology not only promotes the development of social productive forces, but also profoundly changes the relations of production. Due to the wide application of information technology and its profound impact on production and life in the era of big data, we need to build a legal framework for personal information protection from the dual perspectives of constitutional law and civil rights, so that the development of technology can be guided by human dignity and the value of human autonomy. The Personal Information Protection Law is the basic law on the protection of personal information in China in the digital age. The human rights clauses in the constitution are the theoretical cornerstone of the right to personal information as a right in public law, and human dignity is the normative basis of the right to personal information as a positive right. The Personal Information Protection Law adopts the proposition that the right to personal information, as a new right in public law, establishes a complete legal protection system. In China, Personal Information Protection Law and Civil Code form a public-private law hybrid approach to personal information protection. The right to personal information further enriches the connotation of freedom and privacy of communication. Among the bundle of personal information right established by this law, the right to informed consent is the foundation, the right to access is the core, the right to portability is the guarantee of personal information self-determination, and the right to deletion embodies the integrity of digital personality. The adoption of the law transforms the right to personal information from a right ought to be to an actual right. In the relationship between the Civil Code and the Personal Information Protection Law, the construction of the right to personal information and the remedies for its infringement should take the Personal Information Protection Law as their starting point. The personal information right established by this law transcends the right in the private law sense or legal interests in criminal law. It is an emerging public law right with a constitutional normative basis, aimed at guiding the development of technology by the value of human dignity. The Personal Information Protection Law embodies the distinctive public law attribute in terms of legislative basis, rights system, and article design. This can also be theoretically explained from the dual perspectives of a fundamental right and the state’s obligation to protect personal information. As the cornerstone of the public law order in the digital age, its function of shaping of the boundaries of public law still needs to be established through its implementation. The Personal Information Protection Law has established an extensive and comprehensive system of rights, and the structure of various specific rights, the way of their exercise, the obligations of information controllers and processors, the liabilities for failing to fulfill their obligations, and the causes of relevant actions still need to be clarified by law enforcement agencies and judicial departments through legislative interpretation or judicial cases.

Institution Foundation of Personal Information Sharing - From the Perspective of Information Identifiability

Gao Fuping

Abstract: The Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) establishes a system of direct utilization of personal information under the control of individuals, but it is questionable whether it provides a channel for the sharing of personal information. Information has different identifiers: direct identifiers are directly linked to the identity of the information subject, indirect identifiers can identify individuals but are not directly linked to their identity, and quasi-identifiers can profile individuals by combining two or more linkable information. The three types of identifiers bring different risks of harm to the rights and interests of individuals. Both anonymization and de-identification provided for in the PIPL are essentially institutional arrangements against the personal identifiable information risk within a particular dataset, which can eliminate the risk arising from the identification of the information itself, but not that arising from profiling. Therefore, in the absence of measures for addressing the risk from profiling, neither the anonymization nor the de-identification under the current PIPL can support the sharing of personal information. Now that the PIPL defines anonymized information as non-personal information, to prevent deregulation, it is necessary to interpret stringently as to whether anonymization meets the requirements of the PIPL, and to make de-identification a legal system that is in line with the requirement of the international community and can ensure the safe sharing and use of personal information. The PIPL should arrange for the consent before processing and the controlling rights during processing according to the role of different types of information in the identification analysis and the possibility for individuals to control or prevent improper identification. What must be removed for de-identification is the direct identifiers, and the consent before processing should also be limited to direct identifiers. For indirect identifiers, a possible path is to allow their use, but at the same time allow individuals to refuse their use (as opposed to consent before processing), and limit their use or the manner of their use by law or industry self-regulation. For other non-identifiable information, the only way to prevent infringement and provide remedies for individuals is to control the identifying and analyzing conduct. This identification control is not intended to absolutely prohibit the processor from performing profiling, but rather to prohibit identification through profiling. In short, de-identification needs to be reconstituted into a controlled de-identification system of “de-direct identifier + identification control” to allow each industry to develop a controlled de-identification mechanism suitable for its own risk and explore security measures for ensuring the sharing and use of personal information in accordance with the spirit of the personal protection law. Only in this way can we, on the premise of controlling the personal identifiable risk, provide an institutional foundation for the sharing of personal information and maximize the social utilities of personal information.

Criminal Policy Pattern in Major Public Health Emergencies

Peng Wenhua

Abstract: It is unfair to insist on moral reason while ignoring or even denying normative reason, or to advocate normative reason while ignoring or even rejecting moral reason. Normative purpose and overall legal order purpose are two different levels of purpose. The governance goal pursued under normal circumstances is to maintain a stable and constant social order. Since the stability and clarity of norms are conducive to maintaining a stable and constant social order, the basic position of criminal law norms in the criminal law system is generally maintained under normal circumstances. In the event of major public health emergencies, the normal social order is broken, and it is necessary to replace the normal normative purpose with the purpose of the whole legal order, so as to restore and maintain the normal social order. The purpose of regulation and the purpose of overall legal order supplement and complement each other to effectively balance the relationship between social ethics and criminal law norms, keep the application of criminal law active and elastic, and fully meet the needs of judicial practice. A criminal policy that abides by the normative purpose but ignores the overall legal order is sometimes not conducive to safeguarding the interests of the social community. A criminal policy that embraces the purpose of the overall legal order but ignores norms may be detrimental to the protection of individual rights and interests of community members. Under the circumstance of normal governance, China’s basic experience in law-based governance is to adhere to the basic position of the mode of criminal policy rules in social governance. Under special circumstances such as major public health emergencies, adhering to the development mode of criminal policy is in line with the central government’s major policy requirements of strengthening and innovating social governance. Under the circumstance of major public health emergencies, the traditional criminal policy is faced with many difficulties, such as the challenge posed by fuzzy management to rule governance, because the traditional criminal policy is relatively poor in the interpretation of conviction and sentencing, so it has difficulties in dealing with the impact of major public health emergencies. At such a time, it is difficult to restore and maintain the normal social order if we adhere to the pure purpose orientation of norms. Implementing criminal policy development mode is the rational choice of criminal policy in major public health emergencies. The development mode of criminal policy requires the extension of legitimate causes in reality, the reasonable adjustment of conviction and sentencing standards, and the expansion of the scope of criminal law interpretation system. Under the development mode of criminal policy, it is necessary to strictly control the scope of application, legally restrict fuzzy management, and effectively limit moral reason and dialectical logic of regulation.

The System Composition of Effectiveness Assessment of Compliance Programs

Zhou Zhenjie

Abstract:Effective implementation of compliance programs is the key to the success of criminal compliance. To realize the institutional objective of the compliance program system and adequately and objectively assess the effectiveness of specific compliance programs, the compliance monitor or evaluator should be a third-party actor that can actualize the ideology of decentralizing crime prevention responsibility, is able to assume legal responsibilities independently, and has the proper professional knowledge and competence. The ‘third-party organization’ provisions, although generally acceptable, don’t fully satisfy aforementioned conditions. Therefore, this article suggests that provisions be added to Third-Party Opinions issued by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the Ministry of Finance and six other related central authorities in June 2021 to enable corporations themselves to choose a third-party organization with legally required qualifications to design and assess their compliance programs and that corporation should cover the cost of the assessment themselves. Assessment objects of course include compliance programs and their implementation. Considering that no official requirements for the contents of specific programs exist so far, this article suggests that the Third-Party Opinions lay down necessary common elements of compliance programs and provide that a compliance program must be able to address specific risks, accord with the size, business scope, etc. of the corporation in question, cover all involved areas and people and update in light of changes and problems during its implementation. A third-party organization can refer to industrial standards when carrying out the assessment. Meanwhile, people’s procuratorates should adhere to the basic stance that “assessment conclusions of the third-party organization are in principle factual judgement and whether to accept the conclusions is a judicial one” and make their own decisions on key issues, which are different depending on whether compliance programs are designed and implemented before or after the commission of investigated conducts, on the basis of the assessment conclusions they receive. From the perspective of facilitating judicial application, this article recommends that third-party organizations rank the effectiveness of specific compliance programs if they consider them to be effective. A third-party organization should follow the principles of adhering to dynamic assessment, emphasizing internal investigation, respecting common knowledge and paying attention to individual cases in the assessment of compliance programs. Although assessment conclusions can only be used as reference by prosecutors in deciding whether to bring up a criminal charge and take or change compulsory measures such as arrest and confiscation of property according to the Third-Party Opinions, this article suggests that the Supreme People’s Procuratorate includes them in the expert opinions provided for in Criminal Procedure Law because they are important sentencing or even conviction circumstances at the stage of trial.

Objective Law and Subjective Law in Administrative Law

Huang Yuxiao

Abstract: There are three basic positions on how to understand the relationship between objective law and subjective law in administrative law. The position of separation of subjective and objective laws holds that administrative law is an objective order construction law aimed at upholding public welfare. Citizens’ personal rights come from sources other than the legal norms on which administrative acts are based and are in a relationship of confrontation with administrative law. This position has the problems of inability to relate illegality and infringement and confusing the relationship between power and rights. In addition, this position also regards the constitution and administrative law, which belong to the same narrow public law domain, as two separate disciplines. The position of combination of subjective and objective laws, which advocates that a part of the claim right should be separated from the objective law to correspond to the legal obligations of administrative subjects, appears in the form of the mixture of the protection norm theory and the fundamental rights theory. Although this position solves the problem of lack of correlation between legitimacy and infringement, it has its own limitations, such as the dislocation of the platform for the application of the constitution and administrative law to the rights of the party subject to administrative act and the rights of the third party, respectively, and the artificial separation of public welfare-upholding administration and private interest-upholding administration. The position of unity of subjective and objective laws regards objective law as the whole set of subjective laws, rights as the results of the decomposition of the objective law, and the objective law and subjective law of administrative law as the two different sides of the same coin. This position is an appropriate view to understand the relationship between subjective and objective laws of administrative law. Under the concept of distributive administration and interest adjustment, the network of various conflicting, opposing and intertwining interests and damaged interests formed between specific or unspecified plural private subjects resulting from administrative legal norms is the true face of the substantive legal relationship, and the substantive rights in administrative law should be uniformly derived from this interest network. Among these relationships, the two most basic types are the opposite interest relationship as the product of transformation of constitutional freedom rights in administrative law and the interchange interest relationship as the product of transformation of constitutional equality rights in administrative law. The correct way to judge the plaintiff qualification in administrative litigation is to appropriately deal with the relationship between paragraph 1 of Article 2 and paragraph 1 of Article 25 of the Administrative Procedure Law and adopt the method of deducing the legal interpretation of “infringement of legitimate rights and interests” from the legal interpretation of “interest relationship”, rather than the reverse method of deriving “interest relationship” from “infringement of legitimate rights and interests”.

Legal Analysis of the First Case of Facial Recognition in China

Lao Dongyan

Abstract:The first case of facial recognition in China has drawn wide attention because it involves not only the question of how to strike a balance between the protection and commercial application of personal information, but also the question of how the law should properly and reasonably distribute the benefits and risks brought about by science and technology. The judgments of the courts of two instances both recognize the natural person’s right to deletion, which is worthy of affirmation; meanwhile, there are also six defects in the two judgments. The judgments tend to support the interests of industrial development in terms of value orientation, and thus have made a selective interpretation of current law in favor of personal information processors. In terms of social effect, such judgments are not conducive to strengthening the protection of personal information, as they are unable to either effectively encourage natural persons to actively uphold their personal information rights and interests when they are infringed upon or form a strong deterrence against such infringements by personal information processors. In judicial practice, three questions relating to the trial of similar cases are worthy of thinking. First, how the judges should make a reasonable interest measurement in a case involving a new technology that can easily cause social risk and whether they can simply compare the conflicting interests represented by the two parties without considering real or expected risks? Second, in new-type cases, should judges make efforts to explore the basic trend of legal development in the corresponding field and try to make their own judgments in conformity with such trend? Third, how to consider consequences in the dealing of new-type cases, so as to truly achieve the unity of legal effect and social effect, and enable the judgment to have demonstrative significance that transcends the individual case? The so-called technology neutrality is a misleading pseudo-proposition because technology not only is within the system of science and technology, but also acts on and shapes the real society in which we live. Facial recognition technology has attracted the attention and caused the concern of the whole society because the public risk it brings overflows far beyond the science and technology system. At the legal level, on the one hand, if a developed technology is mainly used for committing crimes, the conduct of developing and using such technology may incur legal responsibility. On the other hand, if a technology can be used for both legal and illegal purposes, the seemingly neutral development and use of technology may become illegal under the condition that the actor has subjective knowledge or intention to help others commit an illegal act. With respect to facial recognition, three adjustments at the level of values need to be made in order to responsibly shape the development of technology. Firstly, to give all stakeholders the opportunity to participate in the process, and to actively consider the demands of all parties involved. Secondly, to fairly and reasonably distribute the benefits and risks brought about by technological development. And thirdly, to adhere to the value orientation of being people-oriented and empowering the people.

Transaction with Benefit: Justification of the Normative Purpose of the Crime of Contract Fraud - Taking the Case of Partial Evasion of Rail Freight as the Focal Point

Cai Daotong

Abstract: How to understand and interpret the “miscellaneous clause” on the crime of contract fraud is a controversial issue in both theoretical and practical circles. One of the focuses of controversy is how to treat the value of “listing” conduct of contract fraud and whether it has the significance of a constituent element. At the same time, how to correctly grasp the normative purpose of the crime of contract fraud is also the key issue in the determination of the regulatory boundary of the crime. The purpose of criminal law regulation of contract fraud in the market field, especially in the commercial field, is to combat the conducts without transaction benefit, namely those that have no transaction sincerity or transaction ability and foundation. The regulatory scope of contract fraud in the market field has logic and rules different from those in daily life. The conduct that conforms to the normative scope of the crime of contract fraud must be based on the common crime of fraud, but the conduct that conforms to the constituent elements of the common crime of fraud does not necessarily conform to the constituent elements of the crime of contract fraud. The legislation on special fraud crimes in the field of market economy, such as the crime of contract fraud, itself indicates the restrictive position of criminal legislation on the regulation of fraud in the market field. The difference between the filing standard of contract fraud and ordinary fraud in quasi-judicial interpretation is a good explanation and proof of this position. In deciding whether the act of evading part of railway freight can be convicted and punished in accordance with the “miscellaneous clause” on contract fraud, teleological interpretation is the most important interpretation principle to be adhered to and the limitation of teleological interpretation is an effective method to stop the hidden loophole in criminal law. The conduct that conforms to the purpose of normative protection should be decriminalized through the limitation of teleological interpretation. The market order and public and private property losses involved in the crime of contract fraud refer to the market order and property losses on the premise of no transactional purpose or basis and lack of transactional efficiency. An effective or efficient contract fraud that meets the purpose of transaction does not fall within the regulatory scope of the crime of contract fraud. According to the requirements of the principle of legality, teleological interpretation should only be used for decriminalization. The criminal law dogmatic research and the understanding of normative purpose of economic crimes are inseparable from the infiltration, nourishment and support by the intellectual knowledge of social science and law. Otherwise, the criminal law interpretation and judicial application of economic crimes may contravene the basic economic law and become fallacious. The act of evading part of the railway freight should not be convicted and punished in accordance with the “miscellaneous clause” on the crime of contract fraud.

Post-Schrems II Case Evolution of Legal Regulation of Cross-border Data Flow in EU and China’s Response

Yang Fan

Abstract: The Schrems II case has a significant impact on the EU’s cross-border data flow legal system, which is built with privacy and data protection as its core and requires that whatever cross-border data flow instrument is used, it must ensure that the third country can provide the level of protection of fundamental rights and freedoms that is essentially equivalent to that guaranteed within the EU by virtue of GDPR read in the light of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. Under the influence of the Schrems II case, the status of the Charter in the field of data protection has been further enhanced, and the EU intends to make it a global standard. The application of appropriate safeguards has become more stringent, and supplementary measures requested by CJEU will increase the compliance costs of entities operating outside the region; EDPB will play a bigger role in data protection but needs to coordinate its functions with the EU Commission; and the incompatibility between EU law on cross-border data flow and international trade law has become increasingly prominent and the EU is in urgent need of more space for the operation of its regulatory power. In light of the Schrems II judgment, the EU has published a new version of Standard Contract Clauses, clarified the additional supplementary measures, made more specific the standards to be met by third country surveillance legislation, and promoted the EU’s digital trade model agreement. However, doubts on the rationality of EU’s regulation model have not been alleviated, especially considering that problems such as the imbalance of multiple values, highly political overtones, and lack of classification of cross-border data remain unresolved. On the basis of the Cybersecurity Law, the Data Security Law and the Personal Information Protection Law, China has now built a preliminary regulatory system for cross-border data flow with security as the core value. But the regulation of cross-border data flow in China still has many problems, such as imperfect supporting legislation, poor operability of rules, imbalance between multiple values, and lack of internal and external legal linkage. On the premise of fully guaranteeing data security, the free flow of data and the protection of personal information should be further promoted. To solve these problems, on the one hand, China should improve the security assessment system of data exit and establish the data classification and gradation management mechanism on the basis of absorbing the EU’s regulatory experience that is reasonable and suitable for its own national conditions and improve the protection level of the individual’s basic rights. On the other hand, confronted with common opportunities and challenges, China and the EU may strengthen international cooperation in many ways, for example, realizing the free flow of data in specific fields through international agreements, and jointly shaping the connotation of important concepts such as “reasonable public policy objectives” and “essential security interests” in digital trade agreements.