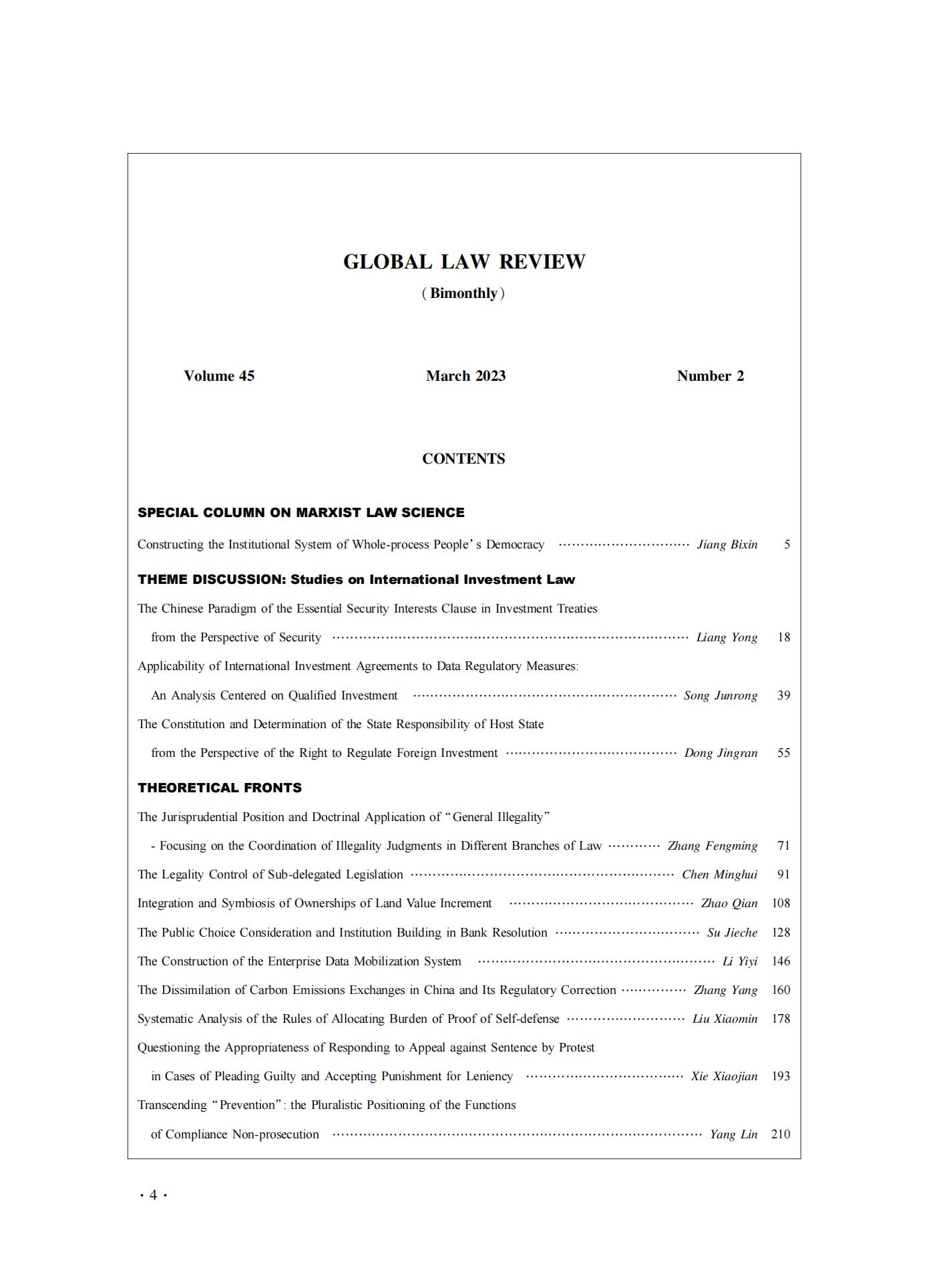

SPECIAL COLUMN ON MARXIST LAW SCIENCE

Constructing the Institutional System of Whole-process People’s Democracy

Jiang Bixin

[Abstract] Whole-process people’s democracy, which is the essential characteristic of socialist democracy, has ushered in a new stage in the construction of socialist democracy in China. To develop whole-process people’s democracy and improve the most authentic democratic framework that enables the people to be masters of the country, it is necessary to integrate Marxist democratic theory with the reality in China. On the one hand, based on the general laws of development of democratic politics, we should recognize the commonalities between whole-process people’s democracy and various other forms of democracy. On the other hand, we should have a thorough understanding of the core and spirit of the “whole process” and fully comprehend the great significance of whole-process people’s democracy of being deeply rooted in Chinese society and culture and able to give full play to the advantage of China’s political system and outperform other forms of democracy. China’s basic socialist economic system and fundamental political system determine the people-oriented nature of whole-process people’s democracy and enable it to surpass the Western nominal democracy and realize the most authentic democracy. To strengthen whole-process people’s democracy and ensure the participation of people without hindrance, we must continuously improve the system of majority rule and attach importance to the protection of the right to equality of minorities in the process of building complete and diversified channels of democratic participation. We must uphold and perfect the Party’s leadership, which is the basic guarantee for developing whole-process people’s democracy and unblocking channels of democratic participation by the people as masters of the country. We must promote democratic consultation with systematic thinking and rule of law thinking, expand participation and build consensus through multi-channel and multi-field consultation. We must follow the principle of fairness and reasonably implement differentiated policies, and protect the rights and interests of minorities and vulnerable groups through concrete institutional arrangements and by giving full play to the role of mass organizations. Whole-process people’s democracy not only is the embodiment of socialist political civilization, but also takes the promotion of the people’s all-round development as its unremitting pursuit. To realize the free and all-round development of the Chinese people and the unity of democracy and freedom in the new era, it is necessary to ensure that the people enjoy extensive and genuine rights and freedoms in accordance with law, and comprehensively advance the practice of law-based governance, so as to provide legal guarantee for the construction of whole-process people’s democracy and the free and all-round development of the people. To promote the common prosperity of the whole people and strike a balance between democracy, efficiency and equality, it is necessary to actively promote democratic political participation, guarantee equal opportunities through broad and equal public participation, adhere to and improve democratic centralism to enhance decision-making efficiency, and to realize fair distribution through institutional decision-making that incorporates public opinion.

THEME DISCUSSION: Studies on International Investment Law

The Chinese Paradigm of the Essential Security Interests Clause in Investment Treaties from the Perspective of Security

Liang Yong

[Abstract] The essential security interests (ESI) clause in investment agreements sets forth an important carve-out for contracting states during security emergencies. As the world enters a new period of turbulence and changes, more non-traditional security elements are included in the scope of overall national security. In response to the increased security concerns of contracting states, the ESI clause in investment treaties evolves in three dimensions, namely frequency, intensity, and breadth. The clause is construed to grant States broad discretion to limit or derogate from obligations arising under investment treaties, providing legitimacy for taking regulatory measures to maintain national security in emergency situations. Although the ESI clause is explicitly “self-judging”, it is still subject to review by arbitral tribunals. However, the variations of the ESI provisions in investment treaties, coupled with the “intentional ambiguities” in requirements of invocation and the “finality” of the tribunal judgments, lead to the “fragmented interpretation” of the clause and may challenge the basis of consensus and stability of investment treaties. The cross-border nature of the ESI clause will make it an important approach to carrying out a China-led strategy of integrated promotion of domestic rule of law and foreign-related rule of law. In the context of non-traditional security, this article analyzes the evolution of the ESI clause in investment treaties, examines a series of Argentine cases arising from the 2001-2003 Argentine financial crisis, two related Indian telecom cases and four recently resolved WTO cases, and discusses the tribunal’s major concerns. It argues that a triangular power balance should be constructed between the self-judging right of contracting parties on ESI issues, the tribunal’s authority to review the legitimacy of invoking the ESI clause, and a certain right of the contracting parties to interpret the review standards. On this basis, the article reveals China’s paradigm of the ESI clause from the following three dimensions. In the textual dimension, China should take its overall national security and self-judging right as the starting point, stick to the security connotation of “clear enumeration + backstop”, introduce leading assessment criteria, enhance its joint interpretation power, and give full play to the role of the preamble as a “safety valve”. In the practical dimension, China should promote the full implementation and internal applicability of the ESI clause in various domestic and foreign-related rule of law scenarios, see security from a development-oriented perspective, and provide a relatively stable context for the application of the ESI clause. In the strategic dimension, China should promote the innovative “China-Model” ESI clause to the world, thereby contributing intellectually to a new generation of more balanced international investment rules.

Applicability of International Investment Agreements to Data Regulatory Measures:

An Analysis Centered on Qualified Investment

Song Junrong

[Abstract] In the era of economic globalization intertwined with digitalization, the data regulatory measures taken by a country not only are closely related to the digital economy industry but also more or less affect other industries. They affect not only the data processing of enterprises, but also the possession and disposition of other related assets in data processing activities, and not only domestic data processing activities, but also related overseas data processing activities. Whether a country’s data regulatory measures are subject to an international investment agreement to which the country is a party depends on whether the measures relate to qualified investment under the agreement. Therefore, it is important to accurately determine whether the data processing activities affected by data regulatory measures contain qualified investment. This involves the determination of whether the data and other related assets in the data processing activities constitute a qualified investment. In addition, special attention needs to be paid to the question of whether the data processing activities affected by a data regulatory measure come from international investment or service trade, which determines whether the measure is subject to international investment agreements or international trade agreements. Under the existing framework of international investment agreements, there are still some uncertainties or irrationalities about the solutions to the above problems, which highlight the deficiency in the identification function of the clauses defining qualified investment in the agreements. As a country of large-scale digital economy, China should provide protection and support for the sustainable development and prosperity of the digital economy while at the same time upholding its right to regulate the digital economy within the necessary scope, and avoiding undertaking excessive obligations. Besides, China should stick to the application boundary between international investment agreements and international trade agreements as regards data regulatory measures so as to prevent the mismatch of obligations under the two types of agreements. As regards the improvement of the clauses defining qualified investment in the international investment agreements concluded by China, the following measures should be considered: (1) to unify the Chinese translations of “asset” and “property” in the definition of “investment” in the English version of the agreements; (2) to add “enterprise” and “property rights regarding data” to the enumeration part of the definition of “investment”; (3) to exclude “market share”, “market access”, “expected returns” and “profit opportunities” themselves from the categories of investment; and (4) to further clarify the spatial, legality and procedural requirements of qualified investment. Besides, China should actively raise jurisdictional objections in relevant ISDS arbitration cases that it may be confronted with in the future.

The Constitution and Determination of the State Responsibility of Host State from the Perspective of the Right to Regulate Foreign Investment

DongJingran

[Abstract] In international investment law, the uncertainty of the constituent elements of the state responsibility leads to obstacles to and risks in the exercise of the regulatory right of the host state. State responsibility is different from contract liability in that it has a significant impact on the international image and status of the host state as a sovereign country in addition to economic burden. The state responsibility of a host state should be based on the Draft Articles on Responsibility of State for Internationally Wrongful Acts and the particularity of the responsibility of a state in international investment law and focus on two constituent elements, namely “the attributability to the state” and “an international wrongful act”. A host state has a dual identity: it is a subject of public law when it violates a treaty, but it is a subject of private law when it breaches a contract, and the two subject identities are inter-convertible according to specific circumstances in international investment arbitration practice. The dual identity leads to the uncertainty of the element of “the attributability to the state” in the determination of state responsibility. The idea of distinguishing between a contract act of the host state and a sovereign act of the host state should become the consensus of the international community and be implemented in the international investment arbitration practice and the reformation of international investment treaties. Public interest and the international minimum treatment standard are the important contents of the analysis of the element of “an international wrongful act”. Public interest is often regarded as an exception to compliance with the international obligations of the host state. The hierarchy of the public interest concerns the determination of the host state’s responsibility. The expropriation measure taken by a host state for an essential public interest should not be deemed as a violation of the international obligation even if it provides no compensation. And the theory of corrective justice and distributive justice plays an important role in understanding the relationship between the hierarchy of public interests and state responsibility. The uncertainty of the international minimum treatment standard leads to obstacles to the determination of the violation of the international obligation of the host state. In determining the international minimum treatment standard, consideration should be taken of the acceptance by the majority of the countries in the international community, especially the opinions of developing countries. Meanwhile, in the context of the trend towards, the “back to the state”, the international community put more emphasis on the host state’s right to regulate. The domestic law of the host state should play a more important role in the judgement of the international minimum treatment standard. The improvement of the system of state responsibility is the basis of the implementation of the Foreign Investment Law of the People’s Republic of China and concerns investment protection as well as the boundary of the right to regulate foreign investment.

THEORETICAL FRONTS

The Jurisprudential Position and Doctrinal Application of “General Illegality”

- Focusing on the Coordination of Illegality Judgments in Different Branches of Law

Zhang Fengming

[Abstract] Many scholars believe that a legal order is a unified whole and cannot give conflicting evaluations for the same act. However, in judicial practice, instead of making general judgments on whether an act is legal or illegal, judges always make judgments at the level of a particular branch of law. In order to coordinate the illegality judgments in different branches of law, it’s necessary to explore whether there is a so-called “general illegality” and what is the relationship between general illegality and illegality in a particular branch of law. Currently, there are three views on general illegality: redundancy theory (RT), antecedent theory (AT) and posterior theory (PT). Firstly, RT holds that the concept of general illegality is redundant in both legal theory and legal practice because it cannot be derived from the requirement of the unity of legal order, and it imposes an excessive burden on judges' work. RT is wrong because the unity of judgment, which is the only reasonable interpretation of the unity of legal order, necessarily implies general illegality, and judges can reduce the burden of judgment through general doctrines and conventions of judicial practice. Secondly, according to AT, the judgment of illegality in any branch of law can be decomposed into two parts: “general illegality” and “fitness to be responded to by a particular branch of law”. The core idea of AT can be summarized as the antecedent proposition and the separation proposition. The former means that any judgment of illegality in a particular branch of law is preceded by a judgment of general illegality, whereas the latter means that the general illegality and the fitness to be responded to by particular areas of law are separated from each other, i.e., “the attitude of the legal order as a whole toward an act” and “whether the act is worthy of legal intervention in a particular way” are two relatively independent questions. The antecedent proposition is false because the understanding of public values depends on the practice in a particular branch of law, thus a judgment of general illegality cannot be made before a judgment of the illegality in a particular branch of law. The separation proposition is also false because there is a necessary conceptual connection between a legal obligation and the way in which a particular branch of law responds to it. Thirdly, PT holds that the judgment of general illegality is a secondary judgment after the judgment of inherent illegality in a particular branch of law, and its point is to introduce justification grounds from other branches of law. The function of the concept of general illegality is to remind judges that the illegality judgment they make represents not only the position in a particular branch of law, but also the position in the legal order as a whole, and therefore all justifications within the legal order must be considered. According to PT, justification grounds can circulate freely among different branches of law, but prohibition grounds remain isolated. The sources of justification grounds are diverse, including the inner morality of a particular branch of law, the political purposes of the state, and the requirements of the rule of law.

The Legality Control of Sub-delegated Legislation

Chen Minghui

[Abstract] Sub-delegated legislation, as a special form of delegated legislation, refers to the act of delegating part or all of the legislative power obtained through delegation to another. Delegated legislation appears in two forms: delegated legislation by decision and delegated legislation by provisions. Sub-delegated legislation often appears in the form of delegated legislation by provisions, so it is more difficult to supervise than other delegated legislation. In China, the State Council and local people’s congresses at or above the level of cities divided into districts have three kinds of legislative powers: inherent legislation, executive legislation and delegated legislation. Both inherent legislation and executive legislation are regarded as primary legislation, and their delegated legislation is not regarded as sub-delegated legislation. Western countries generally impose strict control over sub-delegated legislation, which is reflected in the legal maxim delegatus non potest delegare. The reason for prohibiting sub-delegated legislation is that it violates the trust of the delegator and the principle of statutory authority. Sub-delegated legislation can also bring about confusion about the validity of different legal documents, leading to the problem of low-level legislation hollowing out high-level legislation. Article 12 of Chinese Legislation Law establishes the principle of prohibiting sub-delegated legislation. However, it prohibits sub-delegation of legislative power only at the national level, but not in other situations. In China’s judicial practice, some parties have invoked Article 12 of the Legislation Law to deny the effect of sub-delegated legislation. However, courts do not support such claims and turn a blind eye to this problem. Some administrative normative documents adopted by local governments through sub-delegated legislation have become the direct legal basis for criminalization. In China, sub-delegated legislation has become a remarkable phenomenon and has had a huge impact on the legality principle of statutory crimes and punishments, statutory taxation and law reservation. In order to bring sub-delegated legislation onto the track of the rule of law, it is necessary to expand the scope of the principle of prohibition of subdelegated legislation and make the prohibition in Article 12 of the Legislation Law a fundamental principle of legislation. Meanwhile, in order to leave room for necessary sub-delegated legislation, exceptions to the principle of prohibition of sub-delegated legislation should be set up, but restrictions should be imposed on the level and method of such sub-delegation. To avoid sub-delegated legislation as far as possible, the delegator may directly delegate the legislative power to the subjects most in need of the legislative power through cross-level delegation, which also necessitates the expansion of the scope of the delegated subjects in the Legislation Law. Finally, people’s congresses should supervise sub-delegated legislation through the review of normative documents submitted to them for recordation, and the court can also play a role in this respect through incidental review of administrative normative documents.

Integration and Symbiosis of Ownerships of Land Value Increment

Zhao Qian

[Abstract] The ownership proposition of land value increment mainly focuses on the allocation of public power and private right in terms of land management power and land property right. Under the guidance of the principle of shared distribution, we should achieve the normative confirmation and integrity setting of a fair, reasonable and priority distribution mechanism for land value increment. Management as a public power and property as a private right gradually show a trend toward staggered interconnection with each other, resulting in a dual structure that highlights the essence of the integration and symbiosis of public and private affairs. The management power of land value increment mainly points to the distribution and management proposition of this type of income between the two types of right holders - public subjects and private subjects. We should first set its goal orientation around the multi-level expression of the fairness goal, the interest goal and the goal of powers and functions involved, and then set its basic principles around the multi-dimensional characteristics of the principle of balance of interests, the principle of equal input of resources and the principle of attribute adjustment involved, and finally set its implementation rules around the diversified normative matters of ownership allocation, guide-localization and proportion distinction. The property right of land value increment mainly points to the attribute positioning proposition of this type of income placed in the rights system of relevant private right subjects. We should first set the basis of its power source around the binary expression of land ownership in the static sense and the power of land planning control in the dynamic sense, and then set its right form around the dual-track structure of property right form in the private law sense and development right form in the public law sense. Then try to clarify the matters of individual guarantee and distribution of corresponding management power or property right in the typical process of the realization of two types of land value increment, namely land requisition for primary land development and marketization of collective operational construction land. Structural adjustment guarantee matters of social security and compensation standard in the management ownership dimension and restraint compensation guarantee matters of use control and ownership replacement in the property ownership dimension clarify the guarantee symbiotic pattern in the process of land expropriation for primary land development. Public welfare extraction intervention allocation matters such as land value increment adjustment fund in the management ownership dimension and reasonable internal control allocation matters between collective economic organizations and collective members in the property ownership dimension clarify the distributional symbiotic pattern in the process of marketization of collective-owned construction land. Based on the above, categorization analysis of the structure of staggered interconnection between public and private ownership of land value increment can provide a relatively self-consistent conceptual analysis tool for the research on the regulation strategy of subsequent shared distribution mechanism.

The Public Choice Consideration and Institution Building in Bank Resolution

Su Jieche

[Abstract] The current bank resolution legislation in China is fragmented and there is no unitary bank resolution regime. As a result, most bank resolution rules are placed in different banking laws and regulations in a fragmented way and no consensus can be reached on the roles of different resolution authorities in bank failures. On the other hand, an international consensus has been reached on the philosophy of bank resolution and related resolution measures. However, due to the difference in the bank system, regulatory regime and political environment, different countries have established different bank resolution regimes. The current financial system and financial regulatory system in China play a significant role in establishing the bank resolution regime. Bank resolution legislation involves the gaming between different interest groups. Both the path dependence theory and the public choice theory reveal the possibility of a bank resolution regime violating public interest in the name of public interest as a result of the undue influence of interest groups in the legislative process. Financial crises in history have been the results of “agency capture”. Even though current bank resolution regimes in most jurisdictions have alleviated the traditional problem of “agency capture”, conflicts of interest among resolution authorities should not be neglected and efforts should be made to reduce the undue influence on bank resolution legislation. The Proposed Amendment to the Commercial Banking Law of 2020 and the Draft Financial Stability Law of 2022 partly absorb the sophisticated philosophy and resolution measures of foreign jurisdictions, but do not change the situation of fragmented bank resolution legislation. Path dependence and public choice are the main reasons for this legislative choice. Different interested parties participate in the bank legislation process and try to influence the bank resolution provisions. The current bank resolution mechanism in China reflects the tendency of giving priority to public interests over private interests, taking the marketization of bank resolution as an important principle and granting broad resolution powers to relevant resolution authorities. Compared with the other interested parties, resolution authorities have special knowledge and administrative resources, leading to their comparative advantages in bank resolution legislation. As a result, other interested parties are unable to play their due roles in the legislation and obtain effective safeguards from the relevant legal provisions. The existence of multiple resolution authorities necessitates a reasonable division of resolution powers among resolution authorities. Institutional competition among different resolution authorities may undermine the establishment of an effective bank resolution regime. Therefore, bank resolution legislation should reduce the undue influence of resolution authorities and private interested parties. Furthermore, an effective bank resolution system should also balance various conflicting interests in the bank resolution process and provide a minimum safeguard for interested parties, so as to avoid acts of risk aversion of interested parties before the initiation of bank resolution proceedings and achieve financial stability.

The Construction of the Enterprise Data Mobilization System

Li Yiyi

[Abstract] How to promote the efficient and orderly mobilization of enterprise data is the core issue in the era of digital economy. Data mobilization under the market mechanism takes data trading as the basic form, but data trading is preconditioned on the relevant subjects having a clear property right to data. At the same time, the data trading market needs certain guidance and supervision to promote the orderly development of data trading activities. Therefore, the data mobilization system requires the law to respond to the issues of data property rights and data trading. Regarding the data property rights system, on the one hand, early researches in China’s academia tended to grant data ownership to enterprises. However, the data ownership scheme cannot achieve the goals of fairness and efficiency and is incompatible with the characteristics of subjective rights and those of the data economy. Clearly defined data usage rights can also meet the need for data rights confirmation in data mobilization and data trading practices and avoid the various problems of the data ownership scheme. It should be considered that an enterprise’s actual control over data based on technical means enables it to have effective control over the data and its mobilization, and, as a result, it can use and license others to use its data. On the other hand, to deal with the issue of the data access right of other subjects, the EU and some scholars in China have proposed a data access right scheme. However, the establishment of data access rights is a method for the state to redistribute the interests of data property through legislative means to ensure the realization of justice when the market mechanism cannot achieve a balance of justice. Therefore, legislation should not intervene if there is no obvious market failure. Regarding the data trading system, firstly, to solve the problem of unclear data trading objects, it is necessary to define the scope of tradable data, stipulate the information-providing obligations of data providers, and clarify the liabilities that data providers should bear when providing prohibited trading data or failing to fulfill their information-providing obligation. Secondly, to solve the problem of immature data trading models, it is necessary to position data trading platforms as intermediary-type data trading service providers, requiring them to undertake certain review and security obligations to reduce transaction costs and give effectively play to the role of platforms in trading matching, security, and other functions. Finally, to solve the problem of the inadequate data trading regulatory system, it should be recognized that the practice of nationalizing private data trading platforms can only serve as a short-term solution. Promoting the joint development of and fair competition among data trading platforms with different ownership structures is an inevitable choice to promote the long-term healthy development of the data trading market. From the perspective of promoting market trust, nationalization is not the only solution. The establishment of a reasonable and standardized regulatory mechanism can also achieve the goal. In this regard, in terms of regulatory authorities, the main work of regulating data trading platforms can be undertaken by market supervision and administration departments or big data bureaus. In terms of regulatory measures, China can draw on the regulatory proposals put forward by the EU Data Governance Act.

The Dissimilation of Carbon Emissions Exchanges in China and Its Regulatory Correction

Zhang Yang

[Abstract] Carbon emissions exchanges (CEAs) are a key infrastructure for China to achieve the “dual carbon” target and address climate change through market-based mechanisms. As emission allowances are neither issued by market players nor designed by trading venues, but formulated by the government, CEAs are essentially a “red market” with a high degree of administrative control. Blessed with the policy dividends of environmental protection, pollution prevention and green transformation, CEAs are growing vigorously in China, but their problems are obscured: (1) in terms of structural layout, CEAs are expanding blindly and lack connectivity under local performanceism; (2) in terms of the main business operation, CEAs have mixed products and inverted business under disguised profit orientation; (3) in terms governance mechanism, due to the lack of legal basis, the position of the self-regulatory bodies of CEAs and the scope of their responsibility are unclear, and the problem of multiple competing regulatory authorities is prominent. Unlike China’s top-down administrative promotion approach, which leads to “decentralized development and spot domination”, foreign approaches to the development of CEAs are mostly bottom-up and market capital-led, following the model of “unified competition and futures first”. Under this model, CEAs are set up rarely separately, but mainly through technology export, product inter-listing and equity acquisition, adding segments to the financial exchanges. However, as a result of such profit-seeking and disorderly expansion of capital, carbon trading has lost its focus and fallen into a vortex in which it is increasingly determined by financial, rather than environmental, factors. China should systematically rectify the deviations in the development of CEAs as a public good in the following four aspects. Firstly, it should clean up in a gradual and orderly manner CEAs established by local governments, retain the seven pilot CEAs and transform them into green exchanges with the trans-provincial system, set up independent carbon clearing entities, and separate spot trading from futures trading. Secondly, it should strengthen the guarantee responsibility and self-regulatory governance of the CEAs, and supplement the mechanisms for centralized bidding, CBAM mutual recognition and crisis management. Thirdly, it should construct a regulatory structure with three separate pillars - namely establishment, supervision and operation - to optimize the allocation of regulatory authorities. Fourthly, it should promote the adoption of the Regulations on the Supervision over and Management of Trading Venues. In fact, the issues identified and concluding recommendations in this paper could have a wider application. In recent years, data exchanges, financial asset exchanges, digital currency exchanges, meta-verse trading platforms, commodity forward and intermediate electronic trading platforms and other new types of exchanges have grown rapidly by following the policy trend. In such a situation, government organs should maintain a prudent attitude. Trading venues might be easy to establish, but their real operation is by no means easy. China still has a long way to go in the construction of financial market infrastructure and related legal systems.

Systematic Analysis of the Rules of Allocating Burden of Proof of Self-defense

Liu Xiaomin

[Abstract] Allocation of the burden of proof of self-defense is not only a criminal procedural law issue but also an important substantive law issue. The recognition by the USA and the UK in the 20th century of the common law rule of putting the burden of proof of self-defense on the defendant was based on the “guilty” presumption function of the definition of a crime. Because a systematic concept containing all the elements related to criminal liability had not been formed in the prevailing criminal theory of the common law system, “defense” was not a value judgment category. A behavior satisfying all elements of the definition of a crime might be presumed “guilty”, and in order to refute the presumption, the defendant needed to prove self-defense. The fact that most jurisdictions in common law countries in the late 20th century put the burden of persuasion of self-defense on the accusing party can be explained by distinguishing justification from excuse. Because justification is a part of the criminal law’s norms of conduct and there is nothing that can establish that the defendant has done anything wrong until the prosecution proves that the defendant has committed an offense without justification, prima facie case of guilt can only be illustrated by both the definition of a crime and the justification, for the which the burden of persuasion must be put on the prosecution. The differences among continental law countries in the rules of allocating the burden of proof of self-defense may be rooted in different understandings of the character of Tatbestand and the relationship between its three strata, the key of which is whether Tatbestand has the function of “guilty” presumption. The burden of proof of self-defense can be allocated reasonably to the prosecution if the value neutrality of Tatbestand can be maintained. Tatbestand’s function of presumption of wrongfulness may explain the defendant’s burden of produce evidence for self-defense. If Tatbestand is further understood as a type of wrongful and liable behavior, a behavior satisfying Tatbestand will be presumed “guilty” logically and the defendant must prove the self-defense to avoid criminal liability. In China, the obscure rules of allocating the burden of proof of self-defense can be traced to the controversy over the relationship between the four-elements criminal constitution and self-defense. A rational choice is to put the burden of proof on the accusing party once the defendant puts forward the procedural proposition of self-defense. Merely establishing a hierarchical criminal system that distinguishes affirmative elements from negative elements is not enough to support the definite rules on the allocation of the burden of proof. To provide stable support to the rules of putting the burden of proof of self-defense on the prosecution, it is necessary to establish the “object-evaluation” criminal constitution, retain the constitution of crime as the upperseat concept of all elements related the criminal liability, and reform the content and the systematic function of the four elements of the criminal constitution.

Questioning the Appropriateness of Responding to Appeal against Sentence by Protest in Cases of Pleading Guilty and Accepting Punishment for Leniency

Xie Xiaojian

[Abstract] The reform of the system of leniency for admitting guilt and accepting punishment raises the question of how to respond to defendants’ abuse of their right to appeal. In many cases, after the defendant pleaded guilty and expressed the willingness to accept punishment, the court sentenced the defendant to a penalty within the scope of the sentencing recommendation made by the procuratorial organ on the basis of the signed recognizance to admit guilt and accept punishment, but the defendant appealed against the sentence, requesting the court of second instance to change the sentence to a lighter one. Many of these appeals were “speculative appeals” or “detention appeals” that abused the sentencing appeal system. To curb the abuse, procuratorial organs have responded to such appeals with protest, which has led to widespread controversy. Prosecutors argue that the appeal against sentencing in such cases violates the litigation agreement, reduces the efficiency of litigation, and proves the involuntary nature of the admission of guilt and acceptance of punishment by the defendant, which led to errors in the first instance verdict. However, the inference of involuntary admission of guilt from a sentencing appeal is inconsistent with the phase characteristics of the system; it cannot be inferred from the appeal that there is some “definite error” in a judgment or order of first instance; the protest does not meet the retrospective character of the object of protest or the requirement of statutory grounds for protest, but can easily lead to retaliatory protest; and by confusing the grounds for protest with the grounds for appeal, it also fails to meet the requirements of independence of the grounds for protest. Moreover, responding to an appeal against sentencing by protest contravenes the value orientation of China’s appeal system, suppresses the defendant’s legitimate right to appeal, undermines the trial system whereby the judgment of the second instance is final, is not compatible with the characteristics of insufficient negotiation between the prosecution and the defense in cases of leniency for admitting guilt and accepting punishment in China, and covers up the problems in the system of leniency for admitting guilt and accepting punishment. Therefore, unless there is more evidence to show that the defendant pleaded guilty and accepted punishment involuntarily, thus proving that the first-instance verdict is indeed erroneous, a protest should not be filed against the verdict. As for the question of how to effectively respond to the defendant’s abuse of the right to appeal, rather than carrying out a reform that restricts appeals, it is better to simplify second-instance trial procedures by focusing on the defendant’s reasons and facts for appeal, speeding up the litigation process, and improving litigation efficiency, so as to respond to appeals more quickly. China should, on the basis of guaranteeing the right to appeal, simplify the secondinstance trial procedure by such means as establishing an appeal reasoning system, limiting the second-instance trial only to the review of the defendant’s reasons for the appeal and the prosecutor’s protest opinions, and shortening the time period of the second-instance trial, so as to prevent the waste of litigation resources brought about by the abuse of the right to sentencing appeal.

Transcending “Prevention”: the Pluralistic Positioning of the Functions of Compliance Non-prosecution

Yang Lin

[Abstract] Compliance non-prosecution is an important criminal procedural incentive mechanism for promoting the practice of corporate compliance governance. The compliance non-prosecution systems in other countries mainly focus on pluralistic functions and set certain hierarchical relationships among the diverse functions in light of their own criminal justice contexts and corporate crime governance demands. In contrast, Chinese criminal law scholars view compliance special prevention as the preferential function when constructing theories on this system. Moreover, the social policy demands of the new era push procuratorial organs to pursue the utilitarian aim of corporate compliance. Due to the partial theoretical construction and the utilitarian aim, special prevention plays a primary and preferential role in Chinese compliance non-prosecution system (“prevention-oriented compliance”), leading to some potential risks: (1) the decriminalization disposition may reduce the criminal responsibility excessively, but the system focuses so much on “prevention-oriented compliance” that it cannot sufficiently compensate for the reduction, which may cause an imbalance between crime and liability; (2) when the system takes “prevention-oriented compliance” as the dominate and preferential function, limited attention is paid to the interest relationships damaged by corporate crimes, which is not conducive to the substantive resolution of criminal disputes; (3) focusing too much on the “prevention-oriented compliance” function may lead to procurators’ overdependence on compliance and abuse of their discretion when making the decision on discretionary non-prosecution. China should re-position the pluralistic functions of compliance non-prosecution on the basis of its essential attribute and future institutional legislation. On the one hand, compliance non-prosecution is in essence still discretionary non-prosecution; on the other hand, its institutional function should not be restricted by the specific utilitarian pursuit set at the early stage of the pilot program, but should advance with the times so as to maintain its vitality of sustainable development. For this purpose, we should draw on relevant foreign experiences and reposition the pluralistic functions of the system, so that it has different functions when applied to enterprises involved in criminal cases, victims, society or the state. These functions include decriminalization, special prevention, punishment, reparation, general prevention, improvement of litigation efficiency and integration of crime governance systems. To realize the multiple functions of compliance non-prosecution, hierarchical relations should be established among its various functions, with decriminalization as its fundamental function, special prevention, reparation, punishment and general prevention as the functions to be pursued, and litigation efficiency and integration of crime governance system as the collateral functions of institutional operation. Its legitimacy should rely on the realization of the balance among its multiple functions on the basis of hierarchical relationships. Based on the value objective of functional diversification, China needs to establish a hierarchical system of applicable conditions, fully understand and accurately apply various attached obligations, and improve procedural safeguard mechanisms for the realization of pluralistic functions.